In this post, I want to closely examine stakeholders attempting to overcome these challenges. If you haven’t visited my post before, I recommend having a look at my previous posts before reading this one. So, where are we in Nigeria?

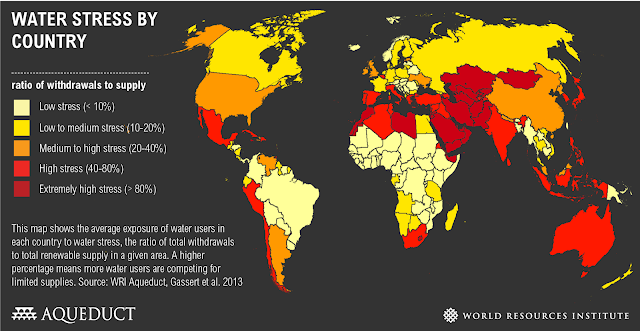

Nigeria majorly struggles in terms of improved water provision. There are different ways to measure the level of water scarcity such as the Water Poverty Index and the Water Stress Index, each providing some interesting figures and rankings though with some downsides (e.g. the Water Poverty Index takes various factors into accounts such as water capacity, access and use though overlooks uneven distribution within the population).

|

| Less than 10% Water Stress in Nigeria?The Water Stress Index leaves out the factors of internal distribution and access. Source: wri.org |

Water security can be defined as a state in which people experience reliable and sufficient access to clean water to meet their needs without having to fear potential hazards and have a say in conflicts arising around water (Chukwu, 2015). According to Water Aid and the beforementioned World Bank report, approximately 67% of Nigerians have access to some basic drinking water service (2017). As outlined, access to water is inherently linked to other sectors such as sanitation and hygiene and a poverty trap. The question emerging is – what can be done about this?

This blog will zoom in on one kind of institution majorly involved in water scarcity in Nigeria - the River Basin Development Authorities (RBDAs).

After gaining independence from the British Empire in 1960, the, then military, Nigerian Government overtook the idea of introducing Water Authorities from the American and British. Subsequently, in the 1970s the first two River Basin Development Authorities (RBDAs), as well as the Federal Ministry of Water Resources (FMWR), were founded by the federal government. Shortly after, there were 11 RBDAs in the whole of Nigeria (Akpabio, 2008). However, while the 36 state governments in the country are in charge of specific sectors, the RBDAs allow the federal government to hold on to a significant amount of power through the federal agencies thus bypassing the state's authorities (William, 2014). We discover the underlying degree of politicalisation of the RBDAs: The governmental institutions in charge of water also function as a loophole in domestic geopolitical power struggles.

After gaining independence from the British Empire in 1960, the, then military, Nigerian Government overtook the idea of introducing Water Authorities from the American and British. Subsequently, in the 1970s the first two River Basin Development Authorities (RBDAs), as well as the Federal Ministry of Water Resources (FMWR), were founded by the federal government. Shortly after, there were 11 RBDAs in the whole of Nigeria (Akpabio, 2008). However, while the 36 state governments in the country are in charge of specific sectors, the RBDAs allow the federal government to hold on to a significant amount of power through the federal agencies thus bypassing the state's authorities (William, 2014). We discover the underlying degree of politicalisation of the RBDAs: The governmental institutions in charge of water also function as a loophole in domestic geopolitical power struggles.

The allocated responsibilities of the RBDAs such as the Chad Basin Development Authority (CBDA) (which was a represented stakeholder in a simulation in a seminar) are diverse. They range from the provision of safe drinking water to the development of irrigation schemes and from the development of navigation and fishery schemes to controlling pollution (Asah, 2014). Further, RBDAs are in charge of construction and maintenance of large-scale water infrastructure projects such as dams. A study conducted on the Cross River Basin Authority (CRBA) in the South of the Country found that the CRBA is majorly underperforming due to a number of reasons which apply for many of the River Basin Authorities. It raises the questions of the effectiveness of the monitoring body of the RBDAs which is the FMWR.

This might change soon, according to an article in the Nigeria Premium Times from 2017, the government intends to commercialise the RBDAs (there are reservations to the reliability of this information since all other online sources found referred to the Premium article). Potentially this will increase the effectiveness of the RBDAs since incentives for private institutions to operate efficiently are pushed through return rates. Providing corruption does not put a stroke in the wheels of this calculation efficiency might rise.

An underlying difficulty which applies here too is the reported chronical lack of reliable data on water sources, use, allocation and contamination which is pre-conditional for adequate planning.

This might change soon, according to an article in the Nigeria Premium Times from 2017, the government intends to commercialise the RBDAs (there are reservations to the reliability of this information since all other online sources found referred to the Premium article). Potentially this will increase the effectiveness of the RBDAs since incentives for private institutions to operate efficiently are pushed through return rates. Providing corruption does not put a stroke in the wheels of this calculation efficiency might rise.

An underlying difficulty which applies here too is the reported chronical lack of reliable data on water sources, use, allocation and contamination which is pre-conditional for adequate planning.

Examining the work of RBDAs exposes the high degree of politicization of water in Nigeria. This starts with the before mentioned lack of true institutional autonomy of the RBDA which poses a threshold for effective work as the agency might, in the worst case, end up as a governmental puppet.

At the same time there are significant levels of corruption within the country (according to Transparency International, in Nigeria $400 billion were lost through corruption in 2012 alone (Ijewereme, 2015)) and the RBDAs (William, 2014). The misappropriation of funding allocated to manage water sources and provision is can have high human costs. Further, we encounter the consequences of water as a politicized commodity. In an institution which is potentially pervaded by corruption, it is favourable to engage in infrastructural schemes which attract high governmental funds – such as dams. If completed, their large dimension can majorly contribute to a derail of the basins development goals with catastrophic implication for the communities affected. In the case of the 1200m long Kiri Dam, for instance, the construction was awarded before a feasibility study was finalized (Salau, 1990). The study later concluded that the dam would eventually result in major negative implications for the downstream regions. The dam was finished in 1982. A study conducted in 2014 found that hitherto, vegetation it the specific region affected had decreased by over 60% causing numerous further negative environmental implications (Zemba, Adebayo and Bauk, 2016)

The politicization of water is, both a crucial and a very common barrier for effective water management in the whole of the country. Internally, the existing basin authorities are in need of far-reaching reforms in order to live up to the many challenges they face. Further, their external embedment in the federal government seems to post new thresholds. Generally, poor data acquisition and high levels of corruption deeply damage the sensible water sector. After all, the fact that Nigeria is so little resilient in terms of water provision makes it easy to call Nigeria's state of water management a tragedy.

With this post, I have reached the end of my series of four posts on Nigeria. Will the country overcome the multi-dimensional barriers standing the way of sufficient water provision? It seems almost out of reach. I personally, consider the deep-rooted corruption, the power of the oil industry and their ties to the economic incentives generated, the domestic geopolitical struggles and the low institutional effectiveness the most drastic factors affecting sustainable water management. After all, it is safe to say that Nigeria’s water sector has a long way to go before being able to supply the entire population with improved water.

With this post, I have reached the end of my series of four posts on Nigeria. Will the country overcome the multi-dimensional barriers standing the way of sufficient water provision? It seems almost out of reach. I personally, consider the deep-rooted corruption, the power of the oil industry and their ties to the economic incentives generated, the domestic geopolitical struggles and the low institutional effectiveness the most drastic factors affecting sustainable water management. After all, it is safe to say that Nigeria’s water sector has a long way to go before being able to supply the entire population with improved water.

Hi Luisa, this blog has been very insightful and has piqued my interest in a very specific subject - thank you.

ReplyDeleteIt's interesting to understand that political, rather than environmental factors are the key issues here. Some silver lining can perhaps be gained from That, as these are things that can be changed with increased political will, and that will only occur with greater publication of the issues, such as you have done here.

Hi Ben, this is great to hear. And yes, good point, if you like "man-made" institutions are key here. However they too require major transformations to tackle issue such as corruption in various sectors which is a grand challenge.

DeleteBesides, It is really nice to hear that this blog sparked your interest in the topics!

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThank you for your interesting series about water management in Nigeria! I enjoyed reading all of the posts.

ReplyDeleteIn addition to the points the other commenters made: In how far do you think are dependencies even after Nigeria got independent from the British still existing today? It is often the case, that no longer states, but rather companies maintain power structures. You mentioned the example of Shell earlier. Would you consider that a neocolonial phenomenon?

Hi Jakob, I am glad you enjoyed following me on this blog. And yes, good point - I would say yes and no - surely, there are strong (western) industries filling space formerly taken by colonial forces. Considering Chinas recent emergence in Sub-Sahara Africa for instance, I would argue that this appears not only as neo-colonial phenomen but as an consistent notion. If you would like to know more about this issue, I found this article https://www.huffingtonpost.com/daniel-wagner/china-and-nigeria-neocolo_b_3624204.html writte by the CEO of Country Risk Solutions very insightful. Maybe you do, too.

Delete