The last two blog posts outlined a number of physical and anthropogenic factors shaping the water sector in Nigeria and unpacked various challenges posed for water protection and management. While human activities and demands severely impact water sources in quality and quantity, physical factors such as high variability in precipitation and thus water supply impact the people and their activities.

In order to further outline the interplay between anthropogenic and physical factors shaping the water sector in Nigeria this post will take further political aspects of water into account. Thus, this blog post will further examine challenges for the equal distribution of safe water. The naturally large numbers of freshwater sources in Nigeria are exposed to different forms of contamination as outlined in an earlier blog post. Moving down the commodity chain, however, that further challenge arises regarding the distribution of the safe water available.

One of these challenges is the strong link between socio-economic status and access to safe water. In the whole of Nigeria, 90% of access to clean water is shared by the wealthiest 20% of households (World Bank, 2017). A study conducted in the Niger Delta States (home to a fifth of the country’s population) for instance, found that overall 85% of the people in the Niger Delta region lack reliable access to safe drinking water (Chukwu, 2015). It appears that higher income households are more likely to be amongst the ones with access to safe water. However, they also spend less on water than poorer households in the same region. This goes back to the fact that higher income household tends to live in estates where piped water is provided at cheaper rates. The water sector thus magnifies the existing income disparity when aggravating circumstances for the poor.

In order to further outline the interplay between anthropogenic and physical factors shaping the water sector in Nigeria this post will take further political aspects of water into account. Thus, this blog post will further examine challenges for the equal distribution of safe water. The naturally large numbers of freshwater sources in Nigeria are exposed to different forms of contamination as outlined in an earlier blog post. Moving down the commodity chain, however, that further challenge arises regarding the distribution of the safe water available.

One of these challenges is the strong link between socio-economic status and access to safe water. In the whole of Nigeria, 90% of access to clean water is shared by the wealthiest 20% of households (World Bank, 2017). A study conducted in the Niger Delta States (home to a fifth of the country’s population) for instance, found that overall 85% of the people in the Niger Delta region lack reliable access to safe drinking water (Chukwu, 2015). It appears that higher income households are more likely to be amongst the ones with access to safe water. However, they also spend less on water than poorer households in the same region. This goes back to the fact that higher income household tends to live in estates where piped water is provided at cheaper rates. The water sector thus magnifies the existing income disparity when aggravating circumstances for the poor.

Through the interdependence of access to clean water and sanitation and hygiene, poorer households are not only more likely to experience water stress. They are additionally disadvantaged through exposure to water-related disease such as diarrhoea affecting children in particular. A number of required federal political frameworks to narrow this gap are not in place or if provided (such as The Federal Government’s National Water SupplyPolicy 2000 promoting the provision of affordable and potable water for all Nigerians) they are insufficiently executed, a recent World Bank Report found (2017). On the state level, the beforementioned World Bank study further found that currently, money spend on the WASH sector is spending in too small quantities and too inefficiently. For instance, it was found that almost half of all borehole constructions projects planned in the period examined were not carried out after all. It appears crucial to emphasize the necessity to consider water not just a technical and ecological commodity but a highly political issue and poverty trap.

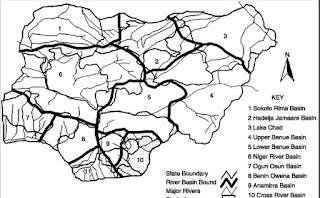

A significant challenge impacting the water sector is posed by the administration. Water management in Nigeria is carried out in the country- the state- and the regional level. Like in many countries, the geographical boundaries of different state authorities are not set according to catchment areas but according to state borders. There are however 11 River Basin Development Authorities (RBDAs), which are shown in the picture underneath. They are in charge of developing, operating and managing allocated reservoir (USAID, 2010). Even more so, the additional number of institutions requires a high level of coordination and cooperation between the 36 state authorities.

|

| River Basin development authorities: Source: Akpabio, 2008 |

A vivid example of the challenges in inter-state management is to be found in the northern part of the country. Around the Komadugu Yobe River system, a tributary of the Lake Chad climate warming, as well as the variability of the river flow, cause less and more diverse run-off. In the upstream region, two dams built in the 70s and 90s are supposed to provide water for irrigation and domestic use despite variability and climate impacts. However, for the downstream regions, these factors resulted in dramatic declines of the annual flow over the years and eventually also contributed to the shrinking of the Lake Chad. The middle- and downstream regions affected by the decrease in water from the river system consider this unfair and demand an evener supply throughout the entire region. In the meantime, farmers affected dug channels to their farms which additionally negatively impacted the drainage network of the basin (Niasse, 2005).

This ‘snippet’ as one might call it highlights the demanding relationship between uneven, thus challenging allocation, corresponding anthropogenic activities and political management. With regards to further external physical and anthropogenic factors outlined in prior posts, sustainable water management appears more demanding than ever. Nigeria seems to face an unimaginable high number of barriers standing in the way of improved water provision for all. The question emerging is: Is there a Silver Lining?

For the sake of brevity in this post, I will dedicate the next post to relevant efforts in the Nigerian water sector. Until then, stay tuned!

For the sake of brevity in this post, I will dedicate the next post to relevant efforts in the Nigerian water sector. Until then, stay tuned!

Hi Luisa, I was really interested by your statistic that 90% of drinkable water goes to the richest 20%, and the attribution of this to the lack of waterpipes. Is the water system (the infrastructure) state-owned, or has it been privatised? Great post by the way!

ReplyDeleteHi, back than it was - which is about to change however, check it out in my next post ;)

DeleteInsightful (and frustrating) information as usual!

ReplyDeleteThank you !

DeleteAgain, an eye-opening - though staggering - post. Thank you! As so often also in Nigeria the poor and marginalized population turns out to be the one suffering from the unequal distribution the most. It is macabre, that people from the upper class spend less on water than the poor. Do you have any ideas on how to get out of this vicious cycle?

ReplyDeleteGood question, Jakob! And, yes-ish there are some schemes which we further looked at in class - for instance is community owned water infrastructure in Cameroon, a potential path in the the right direction. This, in short, cuts out the contracter which would usually benefit from the peoples bills. Instead, all maintanance and provision is conducted by the communtiy. Though, this only works in villages, in which members are interested in this scheme and willing to get involved. I personally find this a very interesting approach and also - judging from our lectures on it - relatively promising, in this sort of small-scale environment.

Delete